Tree Photo courtesy of Andy Bamford

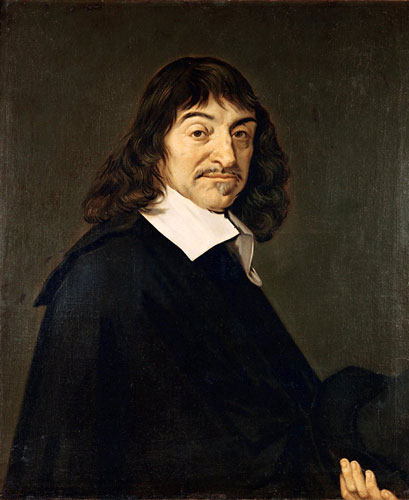

The French philosopher, Rene Descartes (1596-1650) believed that animals were automata. Just fleshy robots with all actions pre-ordained. He wasn’t even convinced that they felt pain. He spent a great deal of his life indoors, and in cold weather he did his cogitating huddled by the stove. One feels his view of the world might have expanded a little if only he had got out more – or had a pet to observe. A Jackdaw, perhaps.

The dictionary says ‘instinct is the innate capacity of an animal to respond to a given stimulus in a relatively fixed way.’ Scientists are increasingly studying the borderline between reflexive reaction and intelligence. Observations of bird behaviour have found that not only can birds communicate and learn from each other, they are capable of being sneaky, playful and innovative; in fact, there is evidence that they think. If you want to read more about this there is a fascinating new book by Jennifer Ackerman titled ‘The Bird Way’.

It used to be an insult to call someone a ‘bird brain’. It now seems that there is no necessary correlation between brain size and intelligence. It has only recently been discovered that birds pack more brain cells into a smaller space. This tight arrangement of neurons makes for efficient high speed sensory and nervous systems. Bird brains have the potential to provide much higher cognition per pound than do mammalian brains.

It is interesting whilst scientists are looking at intelligence in non-humans, there is more research into the instinctive side of humans. It is misleading to be too either/or about this but during our present Covid crisis it has been widely noticed that humans have ‘instinctively’ turned to nature. It is believed that we all have an innate tendency to connect with nature – honed over millions of years – which the psychologists call Biophilia. Being separated from nature harms us.

Mike Rogerson – an environmental psychologist has used EEG sensors to study people’s brain patterns when near trees. There patterns are similar to those of people during meditation practice.

Oaks are apparently particularly effective at calming and connecting with humans; being with oaks is good for us, in ways that are only now being studied. Which is very lucky for us as this part of Surrey still retains many of its mature oaks.

Oaks are also good for wildlife; they support more creatures than any other tree species. Early one morning, returning from ‘oldies hour’ shopping at the Coop, I paused and leant against the magnificent large oak near the tennis courts. I was thrilled to see a tree creeper exploring the crevices in the bark. I would like to give this tree a name as it seems to me special trees deserve a name – there is the Lingfield Oak, the Wymondham Oak, the Selbourne Yew, the Chiddingfold Thorn and so on. How about the Cranleigh Oak or Tennis Court Oak? Perhaps you will be surprised to know that it hasn’t been possible to put a Tree Preservation Order on this tree. I have tried. I hope that by raising awareness of this magnificent tree, we can keep it safe, and that no one in the future will decide that it is ‘in the way’.

We have regular maintenance days at Cranleigh’s Conservation Site at Beryl Harvey Fields. We would welcome more volunteers. Contact Philip Townsend at: for details.