by Joy Horn // Main Image – Baptist chapel in 1932: the ‘schoolroom’ was a detached building at the back

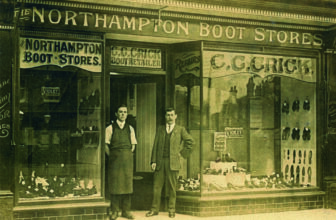

At the foot of this advert for Dan Clare’s chemist’s shop, in small print, is the name of a woman who with her sister made a big contribution to the war effort in Cranleigh during the Second World War. Muriel Clare the chiropodist and her sister Mary organised a wartime canteen for the armed forces stationed in Cranleigh. This operated from 1940 to the end of the war in 1945, in the hall or ‘schoolroom’ of the Baptist church. Muriel made a tape-recording about it and this article is based on that.

During the war, many servicemen stayed in Cranleigh for short or long periods, some in tents on the Common, others billeted with families: ‘Cranleigh was bursting at the seams’. The canteen was used by many from the Royal Air Force, the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force, Dutch airmen, Canadian airmen and engineers, the Land Army, Merchant Navy, Red Cross nurses from convalescent homes at Knowle and Alderbrook, and others.

‘From 4.30 to 10.00pm, seven days a week, the schoolroom was usually full of people. Some would be writing letters at a large circular table, others playing table tennis or engaged in a darts match. Someone was usually playing the piano. Meals were being eaten, with much chat going on, helpers frying sausages and eggs continuously – 60 dozen a week – with waitresses trying to get the right orders to the right people.’

‘Hot meals were served for the first two years, then when food got scarce, sandwiches, buns and our very special Blitz Rissoles (secret recipe). Also vegetable soup, so appetising that men came miles for it.’ Prices were very low, and food was free on Sundays, but because of the large numbers, hundreds of pounds were raised and given away to ‘worthy causes’.

On one memorable day, the 1st Gloucestershire Tank Regiment were pulling out, but ‘we were sent the tip that although they would not be coming to the Canteen, the 2nd Gloucestershires were moving in the same night. So we made no alteration to the amount of food ordered. To our consternation, the latter came in in hordes, but the former also stayed for another 24 hours. That very day, our baker, who was usually very accurate, left in error 20 double loaves instead of ten as ordered. We just felt the Lord had provided that bread. And how we worked that night! Fellows meeting fellows from their same home town, Bristol.’

The canteen was staffed by volunteers. About 40 people were on the rota, many giving up two evenings each week to come. These were ‘members from this church and congregation, and lots of other people living in the Village who were only too glad to help. They were very staunch. There were two men, Mr Cleaver and Mr Fred Warren [of the local builders’ family], who came every day. We could rely on them to act as cashiers, play games or even wash up, wait to the end to see us out, and lock up. We valued them highly. We had no staff troubles throughout the five years.’

‘In those war years, there was a wonderful feeling of friendship. Folks seemed nearer to each other. We had lots of fun. There was a night when an enthusiastic worker let the fat catch fire in the frying pan, and the flames shot up to the clock over the gas stove. Screams from the ladies, and the Army took over.’

On another occasion, a helper cooking chips poured the fat into the wire basket without the pan underneath. ‘We slid for weeks.’

‘On the night a Doodlebug fell on the Cranleigh gasometer, the windows of our schoolroom blew in on the sandwich selection – glass everywhere.’

The Military Police were not popular among the regular soldiers. ’A Red Cap sat down at a table, only to find everyone else left it. We found him a permanent place among the sandwich-makers, and he was glad to sit and talk to them and forget his isolated position.’

‘Then there was a lad with a terribly bad-fitting tunic, and going to be married at the weekend. He sat in his shirt sleeves, while M.A.C. [Mary Clare] got to work on his tunic, taking in a reef all the way down the back, and away he went cheered up.’

‘An air navigator sat in a daze at the writing table until Lights Out, and we suggested that he went back to camp. He told us that his tent pals had gone to Germany last night and not returned, and he just couldn’t, and wouldn’t, go back to the aerodrome and be in that tent alone. After finding out that he was not on duty until 9.00am, we took him back home, where he was cosseted up and talked to, had a good night’s sleep in what to him was a super bed, and by 8.30am he was on his way back to the aerodrome, feeling he had got a grip on himself again.’

‘A wonderful day came at last. A few from our canteen had the privilege of helping with teas in the hangars at Dunsfold, where planes were coming in one a minute for three days, flying home the fellows from Lüneburg [?] prison camp. They were deloused on landing, then given a wonderful tea, before being sent off to rehabilitation camps and then to their homes. They were in pretty poor shape, but deliriously happy. And so were we. How good it was to think of the war being over!’

The Cranleigh History Society meets on the second Thursday of each month at 8pm in the Band Room. The next meeting is on Thursday November 14th, when Sarah Pettyfer will speak on ‘Occupants of Oliver House and Spittleditch’.