The Victorian Schoolroom in Sainsbury’s car park (viewed from the south)

This month we begin a series on ‘Cranleigh Buildings with a Story’.

Have you ever noticed a little building with a slate roof, looking out of place in Sainsbury’s car park? This is its story.

In the nineteenth century, education was neither compulsory nor free. In Cranleigh, many young people getting married signed their names in the parish register of marriages with a cross instead of a signature as they could not write. It has been estimated that only about one in four of the people here was literate, and the presence of four or five small private schools made little impact.

The newly-built National School, about 1850, complete with its bell

The Village School was built in 1848 with donations from public-spirited people and help from the National Society for Promoting the Education of the Poor. Hence it was known as the National School. It consisted of a single large room, with living accommodation for the Schoolmaster and his wife at the back. Parents had to pay a small sum for each child. It was closely linked to the parish church.

The Baptist Schoolroom (north side), in its time as a Mission Hall, 1885 – 1904 (David Mann & Sons archives)

It was probably the opening of the National School that encouraged the Baptist church to start its own school. In 1858 it built an extension to its premises on the Common (behind Chapel Place) to serve as a schoolroom. It must have been fairly cramped for the 32 pupils who were there in 1867. David Mann, founder of the Cranleigh store, received all his education here, and became a well-read and successful business man.

Children playing truant: notice the slate carried by the second boy. An illustration from Isaac Watts, Divine Songs for Children, in a 19th-century edition.

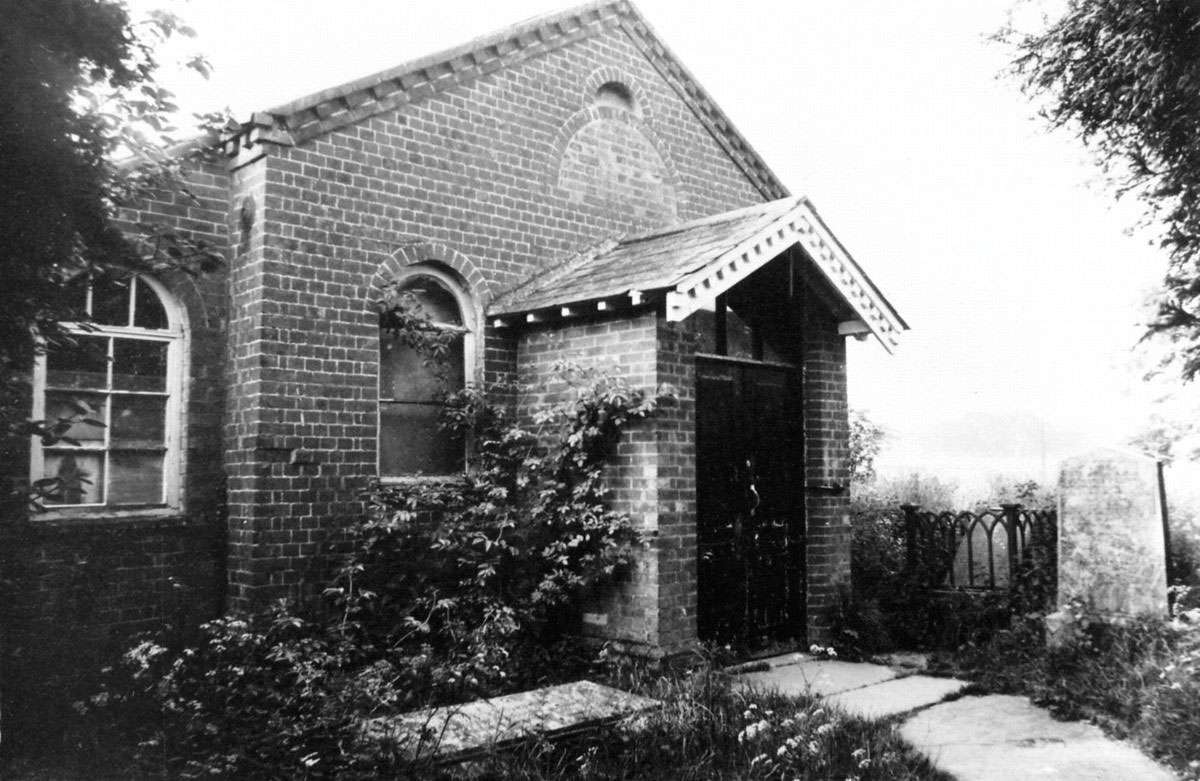

As the church grew, the school needed more space, so a purpose-built schoolroom was erected next to the railway station yard in about 1867. This is the building that can still be seen, by the side of the car park.

The schoolroom was put up by the building firm started by the church’s pastor, George Holden, and by then run by his son Ebenezer. Its walls were single brick, and it was tile hung, with a slate roof. There were no windows then on the south side: perhaps the railway would have been too distracting for the schoolchildren. There were five windows, however, on the other side. The pine floor rested on very old oak beams, with many notches cut into them. Holden’s firm (which specialised in oak) was evidently reusing old timber, maybe even from ships.

The original Baptist chapel (1828), with the schoolroom built on to the side of it

All the pupils would have been in the one room, sitting on forms, with the youngest at the front – the first form. The basic curriculum was Reading, Writing and Arithmetic, with strong emphasis on memorising facts and tables.

Pupils were expected to learn their lessons and repeat them back to the teacher, or perhaps to a monitor or pupil-teacher who was learning on the job. They wrote with chalk on a wooden framed slate. Girls may have learnt some plain sewing, and we know that one girl was knitting an antimacassar in 1867. (Anti-macassars were decorative coverings that were draped over the backs of armchairs to prevent the ‘macassar oil’ that gentlemen put on their hair from staining the upholstery.) Discipline is likely to have been strict, with punishments such as standing in a corner, sitting on a dunce’s stool or wearing a dunce’s hat. One former pupil recalled that when Mr Holden entered the schoolroom, ‘he was in the habit of boxing the ears of the boys, remarking, “If they don’t deserve it now, they will before long”’.

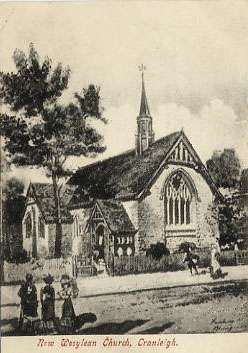

An early postcard of the Wesleyan Methodist church, with the Victorian schoolroom visible at the back (courtesy of Roy Pobgee)

In Alice in Wonderland, published in 1865, Lewis Carroll poked gentle fun at the schools of his day. He parodied one of the moral songs written by Isaac Watts, ‘How doth the little busy bee / Improve each shining hour’, as ‘How doth the little crocodile / Improve his shining tail’. The Baptist church enjoyed singing the hymns of Watts, like ‘When I survey the wondrous cross’. The day school was very likely to have taught his ‘Divine Songs for the Use of Children’ too.

The teacher’s salary and the school’s running expenses were borne by Charles Barclay Barringer, the Baptist church pastor after Holden. Fortunately, he was a man of considerable means, who lived at The Cottage (now Stanford House) on the Common, from where he could see the school, before the intervening buildings were built. Eventually the school expenses became too great, and the school was closed about 1883. The existing pupils, sixty to eighty of them, transferred to the National School. They can be identified in the School Admissions Book, by the entry next to their names saying ‘No Catechism’.

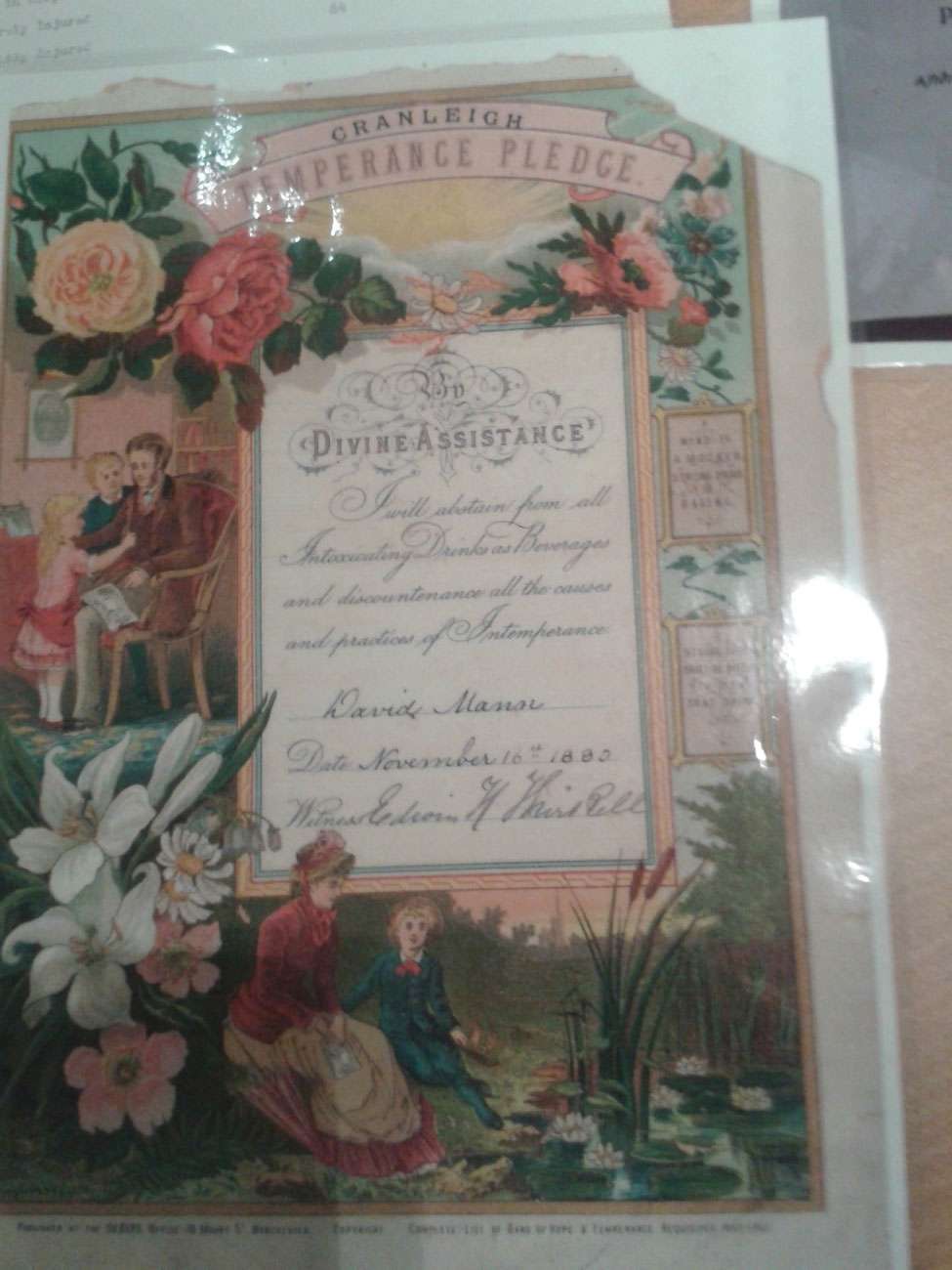

A temperance pledge, signed by David Mann in his late twenties (David Mann & Sons archives)

After this, the schoolroom became a Temperance Hall, and then a non-denominational Mission Hall. When the Wesleyan Methodist church was built in 1904, it incorporated the old schoolroom as its church hall, as it is today.

(For the record, education became compulsory for all children aged 5-12 in 1890; it became free for all from 1891.)

The Cranleigh History Society meets on the second Thursday of each month at 8.00pm in the Band Room. The next meeting will be on Thursday January 9th, when Brian Freeland will speak on ‘Richelieu: the Cardinal and his City’, preceded by a brief AGM at 7.30.