British troops blinded by gas on April 10th 1918 at an Advanced Dressing Station near Béthune (Imperial War Museum)

British civilians faced more and more restrictions in support of the War effort. The ‘Curfew order’ that came into operation on Tuesday April 4th specified that no lights were to be used on shop fronts; no hot meals were to be served in hotels, clubs, restaurants or public eating houses between 9.30pm and 5.00am; lights in the dining rooms of such places must all be extinguished by 10.00pm; and in places of amusement performances must close in time for the lights on the stage or in the auditorium to be extinguished by 10.30pm.

On the Western Front, the Germans’ Great Spring Offensive was making large gains – in some places it broke up to 25 miles through the Allied lines. Paschendaele, won by the Allies after months of costly fighting, fell again to the Germans. Paris was shelled from only 75 miles away. Vera Brittain, working as a nurse at Etaples, wrote in her Testament of Youth, ‘into our minds had crept for the first time the secret, incredible fear that we might lose the War’.

The Railway Hotel, one of the Cranleigh establishments which were not allowed to serve hot meals after 9.30pm. It changed its name to ‘The Cranley Hotel’ in the late 1920s.

Cranleigh man Rennie Crick of the Royal Army Medical Corps experienced the force of the German onslaught at Béthune, a town about 45 miles southeast of Calais and 21 miles west of Lille. His diary entry for April 9th reads: ‘Fritz shelled Béthune and the roads all round it, and it was a terrific bombardment. We had to pack up and be ready to move at once, for rumour said Fritz was advancing towards Béthune. All the civilians ran away!’ Two days later, Rennie wrote: ‘Another heavy bombardment all day, and all our Ambie (the 34th Field Ambulance) packed up and marched away, leaving 18 of us behind. Fritz reported to be only 4 miles away from Béthune! It is like a dead city tonight.’ The next day, Friday April 12th, ‘We left Béthune at 10am, and there were not any people left in the town. Fritz was shelling it very heavily as we cleared out. Marched 4 kilometres back.’ A few days later, he reported, ‘Plenty of casualties came through our Ambie.’

Osbourn’s garage, about 1913, where the Esso petrol station is now

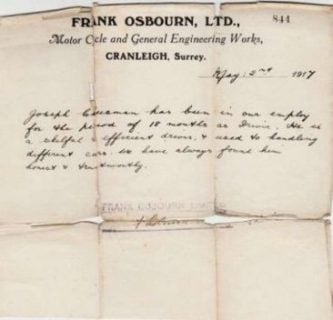

Another young Cranleigh man was caught up in the German offensive. He was Joe Cheesman, aged 18, of Victoria Road. Before being called up, Joe had worked at Frank Osbourn’s garage in the High Street. He arrived in France for the first time about April 1st, with the 3rd Glosters. The German offensive had caused a fair amount of chaos, and at Rouen he was transferred from the 3rd to the 8th Glosters as reinforcement. Then suddenly on April 10th he was sent into the trenches, probably in the area of the river Lys in Belgian Flanders. It was a baptism of fire. On Easter Sunday, April 14th, his battalion was overwhelmed by the German onslaught, nearly all his pals were killed, and Joe himself was surrounded and captured the next day.

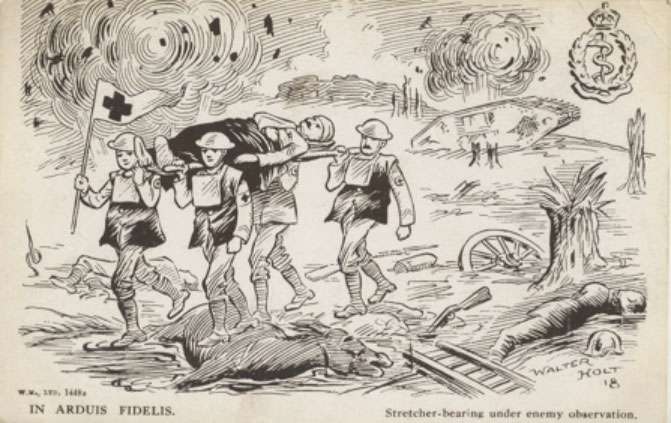

Card from Rennie Crick’s papers showing the bravery of RAMC men in 1918 (by kind permission of Colin Crick, his son)

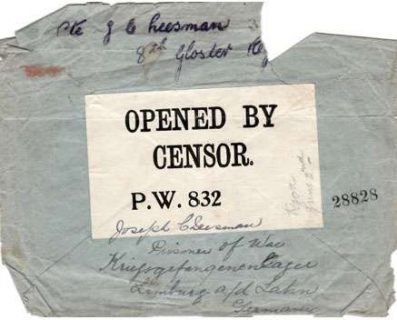

On Thursday April 19th, his captors gave Joe pencil and paper, and allowed him to write home, although Joe knew that a German censor would read whatever he wrote. The letter took until June 2nd to reach his anxious parents, Christopher and Ruth Cheesman. Joe wrote that he was not in a prisoner-of-war camp, but because he was a motor mechanic he had been picked out, with seven others, to work in a depot on keeping German transport lorries roadworthy. ‘Tomorrow is my birthday, too. I didn’t expect to spend it here, but might do so in a worse place, so I’m thankful. The people here are kind and give us fags etc. when they see us.’ (Presumably this means the Belgian civilians.)

The Cranleigh History Society meets on the 2nd Thursday of each month. The next meeting will be on Thursday 12th April, and will take the form of an outing to Clandon Park. Meet outside the house at 2.30pm.

(Left) Back of envelope, with Ruth Cheesman’s additions (We shall follow his story, as told in his letters home, in the coming months.)

(Right) Joe Cheesman’s heavily-folded reference from Frank Osbourn Ltd (by kind permission of Mrs Jill Wood, Joe’s daughter)

No. 6 Victoria Road, formerly called ‘Nethania’, home of Joe Cheesman