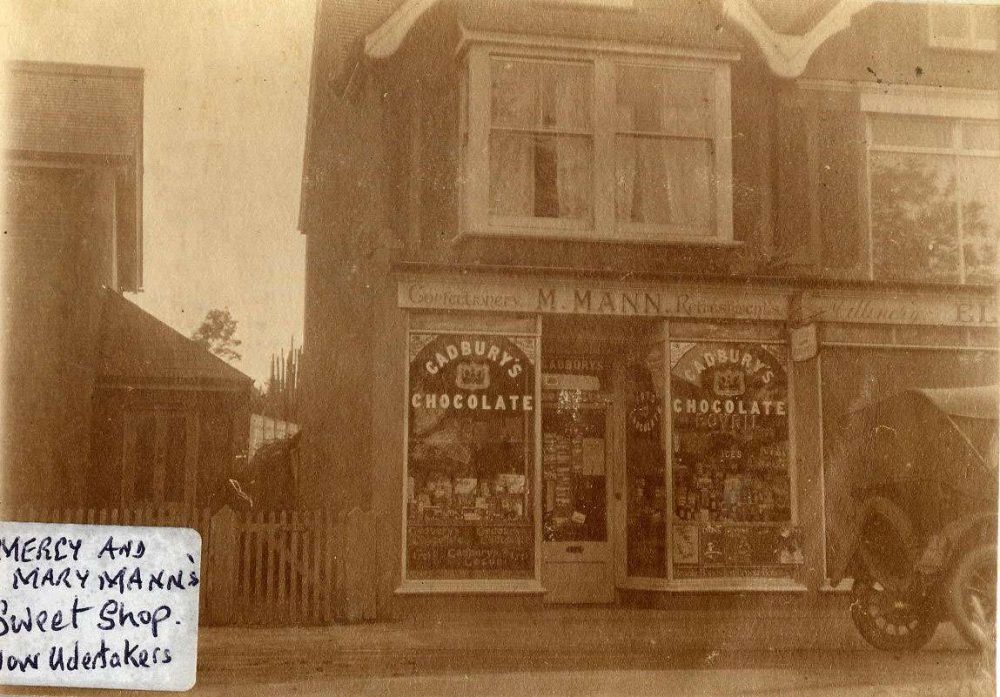

The shop run by the Cheesman children’s aunts, Mercy and Mary Mann, in Dorset House (now Pimm’s Funeral Service)

After two agonising months without any news of their son Joe, on June 2nd Chris and Ruth Cheesman of Victoria Road received a letter from him. It had been written on April 18th. The good news was that he was alive, although a prisoner in German hands. ‘I cannot tell you how thankful we were to get it, and in your own handwriting too,’ wrote his mother. ‘Everyone has been so anxious, and yesterday morning some of the chapel friends were crying tears of joy, when they knew we had heard from you.…As for our children, they seemed like birds let loose. One went one way and one another to tell their Aunties that we had heard. Every one wore a smile on their face.’ (There were at least six Aunties to visit.)

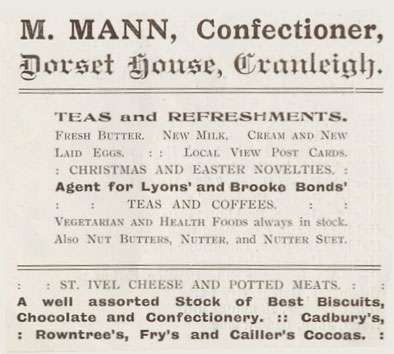

An advert for the aunties’ confectionery

Even after hearing from him, Ruth and Chris’s letters addressed to him at ‘Kriegsgefangenenlager, Limburg an der Lahn’ did not reach him. The Post office returned them and official bodies such as the Red Cross and the Central PoW Committee told the Chessman’s that the address was inadequate.

Meanwhile Joe, who was being held in Belgian Flanders, was longing to hear from home. He was allowed to write a letter on June 2nd, and said, ‘I don’t think I have ever wanted a bit of paper with some writing on it so much as I do now … I am just longing for some news and something English and homely.’ He was still being employed as a motor mechanic, rather than being in a camp. The Great German Advance had now stalled, but the PoWs had not been told this. Instead, he wrote, ‘I hear that the Germans are getting near Paris. I don’t know whether it is right or not, but I don’t think the war will last much longer. Wait till it ends – I’ll soon be making tracks for Cranleigh, I know.’

Joe Cheesman in uniform (by kind permission of Mrs Jill Wood)

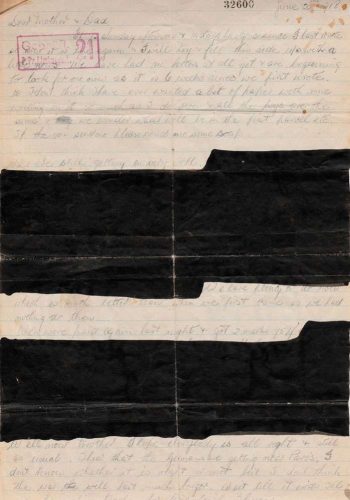

Something that Joe wrote displeased the German censor, because he blacked out two large sections of the letter. A small printed note was attached to it: ‘The British Censorship is not responsible for the mutilation of this letter.’

However, Joe was able to give some more cheerful news. ‘We have managed to get some wood and made a draught board and draughts, which is a treat for a game in the evening, and the Germans play it too. The bootmaker has been up and borrowed them this afternoon.’

(Left) German censor’s work on Joe’s letter of June 2nd

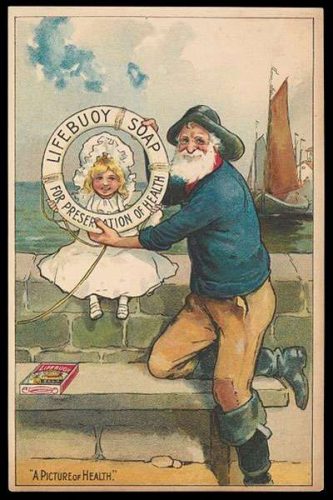

(Right) Early 20th-century advert for Lifebuoy soap

Later in June, he wrote home again. ‘I am still alright, in the best of health, and still at the same place with the same party. We have plenty of work to do with the lorries. I have been working in the shop practically all my time. Our food is still good, although we pine for a bit of English cake or something like that. The only thing we have a job to get is soap. Could you send me some soon? I can’t get on without it, nohow! ’

Pierrot groups like this one suddenly became popular during the war

Meanwhile, Rennie Crick, whose home at the Northampton Boot Stores in the High Street must have nearly backed on to Joe Chessman’s in Victoria Road, was now stationed at a Casualty Clearing Station at Bruay, south of Béthune, and having survived the force of the German Spring Offensive, he was now finding life somewhat easier. ’Not many cases coming in’ he wrote in his diary on June 5th. Instead, he was watching or playing a lot of football and being entertained by various revue groups, often of Pierrots.

This is possibly the OTC PE display of summer 1918

There was no organised gathering of Old Cranleighans this year at the school at Whitsun, as normally happened. This was due to the ‘difficulties of obtaining food and such things’. However, in Red Cross Week, the Lord Lieutenant of Surrey inspected the Officers’ Training Corps at the school. A display of massed physical drill was staged.

The Cranleigh History Society meets on the second Thursday of every month at 8.00pm in the Band Room. The next meeting will be on Thursday June 14th, when Nicci Pugh will speak on ‘From Trafalgar to the Falklands’.