The Brooking museum teaching gallery for historians, students and researchers

I was born in Sutton, South London, in October, 1953. My mother, Edith, was a picture restorer and had run an amazing gallery, known as St. Martin’s Gallery, off The Strand, London. She ran this with her uncle. The gallery was well known and was an ‘Aladdin’s cave’ of paintings, water-colours, china and curios. She closed this shortly after her uncle died and married my father, Arthur Brooking, in 1951. He was an extremely bright financier and something of a business tycoon.

They settled in South Cheam, a highly regarded area of fine ‘Arts & Crafts’-style villas with tree-lined avenues. This setting was to inspire me from at least the age of two. I was fascinated by all types of designs, often in the smallest details, from the leather eyelets of my harness to broken coloured china I found on afternoon walks. My first real ‘craze’ (as they were known in the family) was for the intriguing revolving ‘lobster-back’ chimney-cowls with their central fins, which I noticed, almost with a life of their own, on afternoon walks. My mother fortunately had a great affinity with me as she knew I had an eye for detail and unusual objects.

Her great passion at that time was picture restoration. She was then acting as the picture restorer for The Army & Navy Stores in Victoria Street, London. This meant that every Saturday she would visit the store to collect paintings, my father driving us up to London in our wonderful 1950s Rover. My poor sister, Rosemary, found these trips pretty boring. I however, found the sights and architecture of London truly riveting.

In the Summer of 1957 I caused quite a stir in our household when, having noticed a battered chimney- cowl lying in a pile of rubble in Sandy Lane, close to our house, the following Sunday when my parents were at church, I persuaded ‘Uncle Eddie’, our marvellous family factotum, to collect this with me. Although aged four, I clearly remember the ensuing row when, having carried this through the house, failed to notice dripping tar from its interior – my clothes and the hall floor were covered with black patches. Although my father was furious, I won him around with the help of ‘Uncle Eddie’ and my mother, by explaining my fascination with the carefully designed fin to catch the wind and the simple but elegant mechanism therein.

Charles Brooking meeting HRH Prince Charles receiving a National Art Collections Award 1987

Other early passions at this time included Bakelite numerals and letters on gates. I was fascinated by the different fonts used. My long-suffering mother offered to replace particularly interesting types I had noticed with new types purchased in the local hardware shop in Belmont. Neighbours became fascinated with my interests and sometimes presented me with numerals and letters.

In 1958 we visited the scene of the great Smithfield fire, which burnt for days. This was on one of our Saturday London trips. The drama of the occasion is still very clear in my mind. The city buildings were very black in those days from the London smogs. My father pointed out the Dennis fire-engines and other details, as he used to visit Smithfield market as a boy during the 1920s.

In 1959 he took me up to the City of London on Boxing Day and showed me the bombed-out ruins that still stood in Paternoster Row. He was a fire-watcher during the war and described the great fire raids. The drama of the ruined buildings with their twisted girders and surviving architectural details made a lasting impression on me. My father explained that one of these buildings, with its remaining ornamental plasterwork, was the book-shop he used to visit as a boy. He then plucked a brick from the rubble with a lump of shrapnel embedded in it – he was beginning to really understand my passion for the history of architecture and, I now believe, secretly enjoyed it.

In September 1959, my father, who was then working as Company Secretary for the Kenwood manufacturing company based in Old Woking, Surrey, was keen to move closer to the area. The family also required a larger house, particularly in the light of my mother’s need for an oil-painting restoration studio.

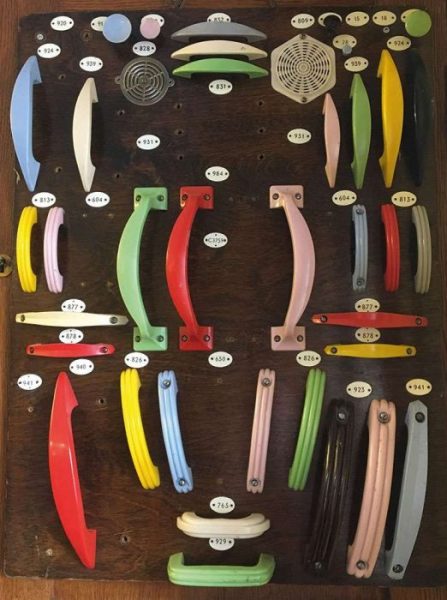

1950s plastic handle display, from hardware shop in Oxshott

After two years of fascinating house-hunting, where I first really became aware of architectural styles, we found an ‘Arts & Crafts’ house built in 1931 in White Lane, Guildford. Interestingly, it was built by the Wood family, who had constructed many prominent houses and buildings in the Guildford area, including the splendid Dennis motor factory offices. I have just discovered that the house has a ‘mirrored double’ in Links Road, Bramley, built in 1926, which was designed by Hodgson & Lunn, a local firm of architects descended from the Henry Peak practice.

Our new house in White Lane, Guildford, being unmodernised, Kenwood’s architects, Malcolm Peck Associates of Friary Street, Guildford, were commissioned to design a ‘state of the art’ kitchen and to modernise the house throughout. My mother, sister and I made many visits throughout the hot Summer of 1959, driving over in her Morris Minor, often listening to The Platters’ ‘Smoke Gets in Your Eyes’ on the car radio, along with Connie Francis. The workmen were very intrigued by my interest and, even more so, at my sadness caused by the destruction of the original maid’s sitting room with its distinctive Tudor-style Minster fireplace and servant-bell indicator board. Mr. Uden, the foreman, who worked for Simmons the builders, was previously involved in the construction of the new Kenwood offices at Old Woking.

He and all the workmen gave me all kinds of fittings, ranging from door ironmongery to the servant-bell system. It was then that I first became aware of the fascinating social hierarchy in house design, particularly in grander houses where servants were employed.

In 1960 I started school at Watlands in High Street Green, Chiddingfold, an enchanting 16th century glass-maker’s house, which had been the home of Sir William Bragg. His lecture room was our classroom. The school was run by Griselle Maxwell, who was keen to encourage my interest in history generally. She explained the history of the house and its connection with Alban Caroe, the son of the famous architect who lived at Vann in Chiddingfold.

An example of the standard of craftmanship that went into making a sash window with internal shutters, rescued from 2 Beach Road, Hayling Island, built in 1828, demolished 1993

The following year in 1961, when an extension was added to this room, I was fascinated to watch Mr. Peak from Dunsfold making the new timber casement windows. This was the catalyst that laid the ground for my passion for all types of windows and doors – the more I looked, the more I saw.

On the way to school I noticed the sad demolition of a large 1870s house on the site of what is now ‘The Meadows’ in Portsmouth Road, Guildford. My father took me down to explore the site at the weekend and it was here that I discovered the wealth of craftsmanship and intriguing ironmongery, such as sash-pulleys, that went into the making of sash windows.

After reading my splendid 1930s ‘World of Wonder’ book, I was fascinated to see an illustration of a complete working sash window. Naturally I was desperate to have a complete example.

In the Summer of 1962 my long-suffering and wonderful mother, Edith, along with our Dutch ‘au-pair’ girl, Anna-Marie, chatted to the foreman of the demolition squad demolishing a row of 1830s houses nearly opposite what is now the multi-storey car park in Sydenham Road, Guildford. My mother offered the chap a Pound to remove a complete window. This was duly delivered the next day and I set about restoring it immediately. I was fascinated by the late-Regency craftsmanship, surviving hand-made crown glass, mouldings, and the accumulated paint build-up over the years. Moving this window around, aged eight, helped build-up my muscles for the ‘rescue’ work that lay ahead!

A vast collection of windows, doors, stairs stretching back in history and into the distance, part of the archive store. In the foreground a Lunette window from Milford House stables 1868 and internal door from 10 Downing Street

At the same time I had developed two major interests in palaeontology and archaeology, and that November, for the first and last time in my life, I succumbed to pressure to conform, by teachers at school and others, and offered to break-up my sash window for bonfire night that year and follow more acceptable interests, such as fossil hunting and archaeology. This new start was soon doomed. I joined a prep. school in Seaford, East Sussex, as a boarder in the Summer of 1963. Normansal School, built in 1905, was a fine ‘Arts & Crafts’ building which set my imagination alight. Interestingly, many old boys from Normansal later attended Cranleigh School. My headmaster was very familiar with Cranleigh as his brother was a pupil at Cranleigh School just before the Second World War, and well remembered the Regal Cinema on Cranleigh common. While at this school I discovered Neolithic and Roman sites on the neighbouring ploughed fields on the South Downs. I soon built up a fine archaeological collection, which greatly pleased my father. I was torn between archaeology and architecture.

In Summer, 1965, my father being very concerned about my problems with maths, employed a brilliant tutor who was an absolute godsend in more ways than one. Edward Wyer was a teacher at Gosden House School, Bramley, throughout the 1950s and 60s. He lived in a delightful Regency Cottage, ‘Little Gosden’, on Gosden Common. He greatly encouraged my interest in architecture and architectural detail, taking both my sister and I to see local buildings of historic interest, including Shalford Mill and Hampton Court Palace.

Edward gave me a marvellous book on Old West Surrey by Gertrude Jekyll. ‘Squire Wyer’, as I called him, was a great fan of William Morris and the ‘Arts & Crafts’ Movement. He encouraged my fascination with the ‘Art Nouveau’ windows at my prep. school, which began to worry my father as he could see the collection moving on to much larger items!

A selection of circular wrought iron windows from Banbury and Ludlow 1840-60s

In October, 1966, when I was just thirteen, I decided to establish a museum of architectural detail. My parents were soon won over to the idea with my tutor’s enthusiastic support. I began to visit the many local fine buildings undergoing demolition that were abundant in the Guildford area at that time as it underwent so much redevelopment. These included early Victorian houses in Dapdune Crescent, Haydon Place, and the old Congregational Church in North Street. On one occasion our German ‘aupair’ girl, Ingrid Beckman, chatted up the foreman of Ebenezer Mears, who were demolishing the above church, and ‘rescued’ a marvellous cast-iron boot-scraper for me.

In the Summer of 1968 the collection was taking over my bedroom to such a degree that my father bought me a fine display shed for it from the reputable firm of Barretts of Ripley. I still have the bill. It was erected in time for my fifteenth birthday that year. Edward Wyer helped me to design the displays therein and presented me with pieces he had found in the stables at Gosden House School, together with a late-17th century wooden door-latch from a house on Gosden Common, which was being modernised.

At that time I was at school at Northease Manor near Lewes in East Sussex. This was a great period of inspiration. I was entranced by the fine Georgian town of Lewes and spent many happy afternoons trawling the bookshops and antiques shops there, not to mention visiting the many fine Georgian houses, then being demolished for slum clearance.

Our school assemblies were fascinating. Leonard Woolf, the husband of Virginia Woolf, would often talk to us about life in Sussex in the past. He lived nearby at the famous ‘Monk’s House’ in Rodmell.

I left Northease Manor in 1971, my parents suggesting that I learn the fine art of furniture restoration, joining ‘Furniture Finds’ run by Stanley Beer at what is now The Bed Centre in Bramley. I worked with Charles Dane for around six months. I found it hard to decide on a career as I was still intent on creating a museum. I was fortunate enough to have space at the family home to continue the collecting work and erected stores in the large grounds there.

During this period I worked at several interesting venues exploring career avenues, including Sotheby’s, Belgravia, R. Holford & Sons, builders of Guildford, to learn about building construction, and British Rail Architects at Paddington.

From 1971 onwards I began to spread my wings and visited the massive redevelopment sites in London, including houses in Piccadilly, Buckingham Palace Mansions in Victoria, and Coutts Bank in The Strand.

Our marvellous gardener, Harold Wakeford, who lived in Chilworth, for a small fee agreed to help me ‘rescue’ the many exciting finds, including 1820s and 1830s fire-grates, in his Land Rover. My enthusiasm set him off on his own collecting spree. He became a great ally, defending me when my father naturally tried to restrain my activities owing to the amount of space my work was now taking up at the family home.

Part of the casement window and fanlight collection, including an example from the Mansion House, City of London 1840s

In 1978 I joined The Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust for a year, helping them build up their Museum of Iron in time for the bicentenary of the opening of the Iron Bridge. This was inspiring work. I became familiar with industrial buildings in the midlands and in Wolverhampton. A local taxi-driver friend, Peter Harmer, also became an ally and drove up to Ironbridge and Wolverhampton to ‘rescue’ my finds. I found driving very difficult, not passing my test until 1989. On many occasions I had no option but to resort to carrying some of my larger finds home by train. On one occasion, when carrying the hob-grate from Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s bedroom fireplace in 99, Gloucester Place, London, one of the fellow passengers on the train from Waterloo to Guildford told me with a laugh that ‘My fire had gone out.’

A local friend whom I had met in 1965 at Sunday School, Robin Stride, kindly wrote a piece describing my work in The Surrey Advertiser in 1972. His father, who ran The Way Ahead driving school, would ring me up, enthusiastically telling me about another building biting the dust. I soon built up a network of friends, both locally and in London, one of whom I met at Coutts Bank. He stored my items for two years in his Victorian house in Victoria Park, Hackney, and delivered them when my parents were away on holiday!

In 1981 I joined The Building Conservation Trust based at Hampton Court Palace. That Autumn the B.B.C. approached me to film the collection for a programme on collecting. This led to many television and radio appearances and, indeed, sponsorship for four years from Scott, Brownrigg & Turner, Guildford Architects, then based at Bradstone Brook, Shalford. It was during this time that I met leading conservation figures, such as Dan Cruickshank, Colin Amery and Gavin Stamp.

In 1985 my father very kindly sponsored the creation of a charitable Trust to safeguard the future of the collection which was now being regularly used by historians and by English Heritage for research purposes.

Ornate wooden door carving, Crimson Drawing Room, Windsor Castle, donated by The Royal Household, 1997

After two very successful exhibitions at The Building Centre in London, one on The History of the English Window and one outlining the coverage of the collection, I was offered a post at The University of Greenwich as a lecturer and space to house the entire collection. The move to the Wapping campus commenced in 1989 and the collection formed a major teaching resource, latterly at The Royal Hospital at Greenwich, where we ran courses on the ‘History of the English Window, Door, Staircase and Fire-grate.’

During the 1980s and 90s, with the help of English Heritage and others, I acquired major pieces from iconic buildings, such as 10, Downing Street, Buckingham Palace, Windsor Castle, and many buildings by leading architects, such as the Adam brothers. However, I must stress the collection is not determined by my taste – I embrace all kinds of buildings up to the 1970s, including the controversial Tricorn Centre in Portsmouth, which is very popular with architectural students who visit the Cranleigh collection.

In 1998 the family home in White Lane, Guildford, was sold. I was very fortunate to find a unique property in Cranleigh purely by accident. This was a former builder’s yard, originally run by Farnfield & Watson, local builders in Cranleigh, and from 1937 by Victor Currier, who built several houses in the area. I moved to Cranleigh in September, 1998. Fortunately my sister, Rosemary, has lived in the village since 1982 and had introduced me to the many fascinating local characters over the years, including Frank Charles who worked for Warrens the builders and was a mine of information about local buildings and history.

Cast iron, early Victorian fire-grate from the drawing room, 22 Stoke Road, Guildford, circa. 1843, donated by the owner 1972

I immediately set about converting the joiner’s workshop on the site to form a display gallery and familiarise myself with the local building styles. I have been very fortunate – many local people have kindly made donations to the collection over the last twenty years. I also act separately as an historic buildings consultant, and as part of my work visit many intriguing historic buildings – from the Tower of London to terraced houses in Malmesbury. I have also managed to preserve features from many local buildings, including Bramley station, ‘Art Deco’ features from the Rex Cinema in Cranleigh, and a cross-section of historic windows dating from the 17th century to the 1950s. Many local firms and builders have generously donated features, along with homeowners replacing their windows. I have been described as a ‘white van chaser’!

In 2011, owing to financial constraints, the University of Greenwich were unable to continue housing the collection and we are now actively seeking a new home. I now have a dynamic board of enthusiastic young Trustees and I have donated the entire collection to the new charity in order to safeguard its future.

I have found Cranleigh an extremely friendly village. It has certainly changed in the time I have lived here – the traffic has noticeably grown. As a conservationist I am concerned that with the inevitable building of new houses that something of the local vernacular is reflected in their design – I am not advocating a pastiche but good modern design reflecting the use of local materials, such as tile-hanging.

Part of the door furniture display, circa 1850-1905

The museum collection has become very well known in architectural circles, largely owing to the unique ‘hands-on’ teaching philosophy I have developed. I was greatly honoured to be invited by Rem Koolhaas, the internationally-acclaimed architect, to participate in the 14th Venice Architecture Biennale, 2014. I restored and displayed 68 historic windows, including local examples, in the British Pavilion in Venice, to illustrate the development of this important architectural feature over the last 300 years. The event was amazing in that it generated great interest from not just the specialists, but from the general public, the Venetians themselves loving it. Visiting Venice is a truly divine experience. This display is shortly to be re-staged at the superb new Velux Window Foundation’s museum in Copenhagen.

I have this vast collection of items that I’ve taken from a wide range of buildings over the years which now needs a building of its own – an educational resource tool. It would be wonderful to find somewhere local.

When the Regal Cinema, Cranleigh, was being demolished the foreman of the demolition company, Comley Demolition, delivered the original entrance doors to the building to my house. Over coffee he told me about a ghostly presence he felt in the building. He was convinced someone from the past was not happy about the demolition and indeed he found the whole job quite distressing. At least elements of this cinema, along with many items from the Guildford Odeon Cinema, where The Beatles performed in 1963, have been preserved.

John, Paul, George and Ringo probably ran up the stairs of the Odeon Cinema, Guildford in 1963, holding on to this very handrail, built 1934

I feel my life has been a calling. The collection gives many people great pleasure – some becoming quite emotional when they see a part or a photograph of a building that influenced their lives in the past. Students often comment on the intriguing range of objects, such as 17th century doors and 1950s Crittall steel windows. Others marvel at the styles represented in the domestic stained glass collection, ranging from the Aesthetic Movement to ‘Art Deco’ and 1950s Rennie Mackintosh- influenced windows from North Wales.

We have many people visiting who are actively involved in the restoration of their house or a building. It is always a joy to learn more about their problems and to advise them on the best way forward in terms of repair and restoration. You never know where you are going to go next in terms of giving advice. The work is never dull – architecture, architectural detail and design is certainly an enriching field.

I would like to sincerely thank all the local people who have helped and donated so much to the collection over the last few years. The rescue goes on . . .

This Japanese mons motif is from a finely-cast Aesthetic Movement parson’s grate of circa 1873-4 made by Barnard Bishop Barnard of Norwich and was designed by Jekyll, who developed this theme for many of their exquisite fire-grate designs.

This example came from the Director’s office at The General Trading Company, Sloane Street, London, originally houses built around 1875, and later converted to their premises in circa 1960. The Director, David Part, told me about this grate when the building was threatened with demolition in 2000, and I recovered it shortly afterwards. This was one of several kind donations to the museum made by The Cadogan Estate, owners of the site. It forms an important part of the fire-grate collection, charting the evolution of the coal-burning grate from the early-18th century until the 1950s.

THE BROOKING MUSEUM OF ARCHITECTURAL DETAIL – Registered Charity Number 1155363

With the *collection now in the care of the new Brooking trustees, I am confident for its future and that its purpose – to tell the story of architectural detail design and making – will reach and benefit a much wider audience. Trustees are currently focusing on developing exciting new programs for local volunteering to help us catalogue the archive, and to raise much needed funding with our ultimate ambition to rehouse both the museum and the archive into one accommodation.

If anyone would like to support us in either aspect, we would be most grateful and you can email us on enquire@thebrooking.org.uk.

Charles Brooking, Historic Building Consultant www.thebrookingcollection.org

* The collection now consists of over one million rescued items from many iconic buildings such as:

Wembley Stadium, Broadcasting House, The Houses of Parliament, Tower Bridge, St. Paul’s Cathedral, St. Pancras Station, Kings Cross Station and Osborne House.

Part of the sash window ironmongery display

THE BROOKING MUSEUM OF ARCHITECTURAL DETAIL – Special thanks for donations go to:

- P & P Glass of Peasmarsh, Guildford, who have donated many historic windows, including elliptical windows from Guildford High School, over the last 25 years.

- Bramley Windows, Bramley, who have donated windows ranging from 1760s examples in Hambledon to fine ‘Arts & Crafts’ varieties from the local area, over the last 20 years.

- The Traditional Sash Window Specialist Co. of Guildford, who have donated an amazing cross-section of sash windows, ranging from the mid-18th century onwards. Most notable recent acquisitions include 1812 bowed sash windows from Bookham Manor School and an important cross-section of imported American sash window ironmongery. The opportunity to visit their yard frequently has greatly increased my knowledge of sash window history and ironmongery over the last 5 years in particular.

- Clement Windows of Haslemere, who have donated an important range of wrought-iron and steel windows, ranging from a 17th century flat-framed casement from Elstead to windows in Modern Movement flats in Palace Gate, Kensington, along with many important ‘Arts & Crafts’ local varieties, particularly from Godalming and Haslemere.

- Jennyfields Windows of Badshot Lea, Farnham, have made important contributions to the collection with some unique metal window types, last week donating early prototype Crittall steel windows of the 1890s from an ‘Arts & Crafts’ house in Windsor.

- The Innovate Design Systems Window Co. of 38, West Street, Dorking, who have in the last 4 weeks just donated unique examples of ‘Arts & Crafts’ bronze casement windows from a fine 1906 ‘Arts & Crafts’ house near Westcott, Dorking.

A Lunette landing window Fleet Street, London, 1902, rescued during demolition 1980

On a more local level I would like to thank The Brookmead Veterinary Surgery for donating examples of circa 1875 sash window ironmongery and sash windows from Brookmead House, Cranleigh, which illustrate high-quality materials of the period, and Betts & Co., builders of Cranleigh, for donating interesting castiron counter-balanced stable windows from the original stables (now demolished) adjacent to The Cranley Hotel.

Also special thanks to Richard Womack of David Manns for donating historic ironmongery reference catalogues, to the museum and Susan Beardmore my fellow collector and partner.