I was born in Tain in Ross-shire in 1936, in Scotland. Tain is a small town (population approx 4,000) in the Ross and Cromarty area, close to the scenic Dornoch Firth and boasts a number of attractions including Glenmorangie distillery and Balblair distillery. Inverness is about a 45 minute drive south.

I was the second eldest child having two brothers and two sisters. We lived there on a little farm, which in Scotland is known as a croft. My father worked at one of the whisky distilleries and my mother would look after the house and a busy young family. Such was life in those days.

My parents sent me off to the local school which my brothers and sisters all attended but I’m afraid I hated school the whole time I was there. There was nothing I enjoyed about it, not even slightly. The happiest day was the day I left at age 15.

This is me aged 16 when I played for the British Legion Pipe Band in Invergordon

I began working on the farm for a few years. Then when I was 18, I went into the army and spent three years with the Seaforth Highlanders. Travelling was a big part of my army life and I ventured to many places; all across Egypt, up into the Yemen Mountains and I finished my time in the army, in Gibraltar. From 1956 to 57.

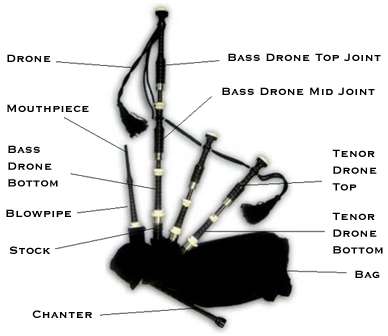

I quite enjoyed my army experience, but the best part was playing the pipes. I started learning to play when I was 10 years old, but it was all forced upon me at the time. My father was a piper and it is rumoured I was born to the sound of him playing his pipes, can you imagine the sound – me crying and my father’s playing? My father found me a teacher who had taught him years ago and he taught me from scratch. Never did I consider at that point, that bag-piping would be my life! I felt I was reborn when I began to play the pipes.

Often when I was very young, I would hear the pipes over the radio, and straight away I felt it in my heart. My dad didn’t play every single day, but I did! Learning to read music took me a little while but I gradually learnt to sight read. My father made it look so easy and was patient with me, it really helped my passion to grow, I was 14 when I began to read music. Once you’ve learnt the music you can memorise it. I used to play for long periods of time up in Scotland. I once took a 20-mile foot march with a fellow piper, playing the tunes as we walked along!

My 1956 leather pipe case

They say it takes about seven years to become a proficient piper, though you continue to learn for the rest of your life. That’s the considered opinion from generations of pipers. My seven years began when I was 14, until I reached my very best at 21 years old.

I remember as a young 16-year-old boy, playing in the Invergordon British Legion Pipe Band which was a great learning experience for me, and they gave you a uniform and pipes for free which was an added bonus! However, I did buy my own set of pipes in 1956 for the sum of £63 plus a beautiful leather case for £13, which was a huge sum of money at the time, from a company called Robertson’s of Edinburgh.

Everything was handmade in ebony wood with ivory and solid silver, engraved attachments. My parents paid most of the money and I put £30 towards it. I still have them today 64 years later!

My engraved present from Mum and Dad

I often hear good people playing pipes but it doesn’t sound right sometimes. It’s something you have to feel in your heart. One day at a friend’s house in Crawley, I was playing the pipes and the best piper in the world, Donald Macpherson, was present. We all took turns to play and he suddenly said, “There’s only one man here who’s playing from the heart, and that’s you John.” I’ll never forget that moment, it was a huge compliment to me.

When I first joined the army, I was stationed at Fort George, one of the most outstanding fortifications in Europe. It was built in the wake of the Battle of Culloden (1746) as a secure base for King George II’s army.

The imposing fort was designed by Lieutenant-General William Skinner and built by the Adam family of architects. Fort George took 22 years to finish, by which time the Jacobite threat had subsided and it has served the British Army for the almost 250 years since. It was here that I learnt my craft of pipe playing no matter what the weather; deep snow, rain, hail, I would get up at 6am and start by playing the piper Reveille, before breakfast. “Reveille” is a bugle call, trumpet call, drum, fife-and-drum or pipes call most often associated with the military; it is chiefly used to wake military personnel at sunrise. The name comes from réveille, the French word for “wake up”. We certainly did wake the troops up!

After breakfast, everyone else would then head down to practice for a time; learning new pieces. Or teaching music to other recruits, practicing for parades until each one of the musicians in turn was relieved of his duties. However, most days, myself and another soldier would keep playing until lights out, from around 7am till 10pm. We loved playing so much we would only stop for meals and rest breaks. Apart from general soldiering duties this routine continued for the best part of my 3 years in the military. I was always playing or performing.

When I left the army I did various jobs; I first went to work in a shop in Aberdeen because there were no jobs near my home. Times were hard. After a while a new distillery was built nearer home so I went to work there. I started off as a boilerman, helping to maintain all the works to keep it running. Then I became a stillman which was the second-best job in the distillery.

One morning I was working alongside a manager who thought he was God’s gift, if you know what I mean and was very difficult to work with. I collected my bag and handed my notice in! In the light of my subsequent discovery I realised it wasn’t my best decision. He’d not been very well and got out of his sick bed at 3am to come around and ask me to stay on. I didn’t drink and he said he could depend on me to do the work, without being drunk, but I stuck with my decision.

You can see where I scratched my name on the chanter

Some weeks later, around Easter time my cousin visited from Edinburgh. He worked as a cooper and assured me there were jobs to be had in Edinburgh. So, I returned with him and got a job at the famous Crawford’s Biscuit Factory.

From there I was encouraged to go to London when a chap I met said, “Go down to London, you just have to step across the road and you’ll get another job.” So, with that comment ringing in my ears, I thought ‘let’s go to London’. My two brothers came with me. One didn’t like it at all and went straight home. The other settled into life down South, got married and moved to Horsham. This was in 1961. He married in 1962. Two to three years afterwards I met my wife Margaret a beautiful English girl and we got married and moved down here to Alfold in 1966, the World Cup year, and we’ve lived in Alfold ever since. We moved into our present house in 1969, and been in it for 50 years. We have two sons, five granddaughters and a great grandson. I’m now coming up to 84.

Fort George main entrance and drawbridge

My first local job was at the concrete workshop in Cranleigh, which was called Sydney Hill. I left there after a while and worked at the Rudgwick Brickyard for 23 years. I still continued piping, at weddings, birthday parties and New Year do’s, (though never any funerals). I once played at seven consecutive Burn’s Suppers in one year. Along with other pipers, I would go down to Brighton on breaks to play pipes with the British Caledonian Pipe band. Some members of BCA travelled all around the world, I only went with them once, to Holland though. I preferred to be nearer home with my wife and family.

I just loved playing the pipes and would come home from work, have a quick shower, tune up the pipes and travel up to London to play until midnight, before returning home. I’d only have a few hours’ sleep, then get up and go to work. It was a busy life but I really enjoyed it.

Fort George from the air

My wife was very supportive of me doing this, she knew how much it meant to me. She came along when we played at carnivals or garden centres. We used to enter competitions as well. I had a full-time job and these events were all extra to my hours of work. We’d get a bit of cash for our services, though I never did it for money, it was a pleasure and I would often play for free.

When I was in the army, we only played the pipes at safer places. We played them up in the Yemen Mountains. I always said as soon as I got out the pipes, everyone would settle down.

I do hear people complaining about the noise bag pipes make. I was playing in a nice posh hotel in Kent once, and this gentleman came up to me and said “That’s enough of that blinking noise.” I replied “Thank you very much, but just listen for a while.” He came back an hour later after giving me more air time and said, “You’re on to something there mate.”

Troops on parade at Fort George

Along with my father, my uncle Tommy also learnt to play the pipes. Unfortunately, he was killed by a German sniper during the 2nd World War in 1940, on the 7th June, two days before my 4th birthday. He was wounded and must’ve tried to escape, but the sniper spotted him. My grandparents and my whole family tried to find where he was buried, which was miles away from where it took place. I was shown photos of him and decided I wanted to be a piper.

Even now when I see a piper, I approach them and have a chat, it’s very moving and inspirational.

One of my proudest moments was being a Guard of Honour for Field Marshall Montgomery, that was one of the highlights of my life, and we played during the General’s salute. There was another time when he came to visit us, he congratulated me as I had bought a brand-new set of pipes which he spotted.

Left to right, me, my uncle Tommy, Dad and my uncle Willie, all Photoshopped together in the one picture

I was the only piper who had bought a new set of bag pipes for the event. Unfortunately, I had to stop playing about 23 years ago when I developed Lymphoma and my lungs gave out. With the first chemotherapy treatment my doctor got it under control, he caught it just in time.

Throughout my life the bag pipes are the only instrument I’ve wanted to play. I play for everyone to hear. I love to teach others how to play, and have taught a few people but not many have kept it going. I taught my nephew, who won the under 16’s competition in Epsom. I taught another boy, Peter Ferguson, who won the under 16’s the following year and also the under 16’s competition up in Scotland, so I must have taught them well.

For anyone embarking on learning to play the bag pipes I would advise them to realise it’s a lifetime of practice and commitment, keep at it and push yourself. I can tell if someone’s good as soon as I hear them play. My friend Iain Craig was the first one I ever noticed that made the ‘big sound’.

My 1956 set of pipes which I still have to this day

Another piper who could produce the ‘big sound’ Donald MacLeod, was a legend in his own lifetime and studied under a chap called John MacDougal for 25 years. Macleod would play for 2 hours non-stop, never playing the same tune twice.

When playing the pipes, you have to memorise the music of each tune, there’s no place to have the sheet in front of you when walking along. It’s no good just memorising it either, you have to play it correctly and blow the proper tone. Anyone can play pipes, but only six men I’ve known in my lifetime that I can recall, and I’ve heard thousands of pipers, can do what I call ‘the big sound’, this great powerful sound. I could never quite get it.

We were walking across the desert, when a mate of mine who wasn’t a piper, heard these pipes and they were beautiful, it was like God’s call, in comparison the rest of them were just a noise. There were 20 others listening and not one of them heard the sound I heard. The Big Sound is the greatest experience I’ve had.

John Newlands, March 2020

Bagpipe History

Up until 1996 the bagpipes were classified as a weapon of war, meaning a physical weapon, like a sword or a musket because of its inspirational effect on the men. This stems back to the Battle of Culloden when a piper named James Reid, was captured by the Duke of Cumberland’s men, put on trial and accused of high treason against the English Crown. James Reid claimed his innocence because he only played the bagpipes and did not have a gun or a sword. The judges however, said that a highland regiment never marched to war without a piper at its head and ruled according to the law, the bagpipe was an instrument of war. James Reid was condemned and subsequently hung, drawn and quartered.

Bagpipes in the WWI Trenches

Did you know the bagpipes played an important role for the British army during World War I? 2500 bagpipe players were in the trenches with their men.

Piper Daniel Laidlaw, when morale was at rock bottom was ordered to start piping, to pull the shaken soldiers together ready for the assault

The pipers played the clarion call to arms to the men of the British Expeditionary Forces and thus were usually the first ones “over the top.” They stood in full view of the German lines, playing their instrument, marching through “no-man’s land” without any sort of ammunition but their sound. The bagpipe players carried no cutting devices when they encountered barbed wire. Enemy fire mowed them down just as effectively as they killed advancing troops. 600 pipers were wounded, 500 bagpipe players died while rallying the troops into battle. They received an extra penny a day to play their pipes.

For the most part, the bagpipes skirled out the regimental tunes to get the men moving, tunes such as Highland Laddie, Bluebonnets Over the Border, and the Minstrel Boy. You can hear twenty tunes here. Some of the more famous bagpipe rallying tunes, The Battle of the Somme and The Bloody Fields of Flanders were written in the trenches on site. Astonishing.

Last Surviving Bagpiper

The last bagpipe player survivor from World War I was Harry Lunan of the 5th Gordon Highlanders. He took part in the assault on High Wood in July 1916.

He described the experience as an honor: “You were scared, but you just had to do it, they were depending on you. In the first assault, I played the tune Cock o’ the North. I played my company over the bloody top, right into the German trenches. It was stupid as hell…Men falling all around me, falling dead…it was bloody horrible. After that, I just played whatever came into my head, but I was worried about tripping on the uneven ground, which interrupted my playing. The enemy fire was murderous, the men were falling all around me. I was lucky to survive. Hearing

the pipes gave the troops courage.”

Lunan’ playing caused a variety of reactions from the non-British troops:

“The French enjoyed the pipes, they couldn’t get enough. They would sing French tunes and I would play them. The Germans were scared of the bloody pipes.”

Lunan died in Canada in 1994, age 98 years old.

Look closely – he’s facing the battle and smoke comes from shells. © Wikipedia

Bagpipes in the WW2

Bill Millin

Piper William Millin, was the personal piper to Simon Fraser, 15th Lord Lovat, commander of 1st Special Service Brigade. Millin is best remembered for playing the bagpipes during the D-Day landing in Normandy Bill Millin whilst under enemy fire.

D-DAY 6 JUNE 1944. The British 2nd Army: Commandos of 1st Special Service Brigade landing from an LCI(S) (Landing Craft Infantry Small) on ‘Queen Red’ Beach, SWORD Area, at la Breche, at approximately 8.40 am, 6 June. The brigade commander, Brigadier the Lord Lovat DSO MC, can be seen striding through the water to the right of the column of men. The figure nearest the camera is the brigade’s bagpiper, Piper Bill Millin. (Wikipedia)

For further information, or view an excellent one hour film, Pipers of the Trenches at www.michelleule.com/2016/01/15/wwi-and-bagpipes/

Hello John ron craig here from New Zealand. Remember the pride of Murray . What an interesting article I often ask ian how you are going. Ian is going through a hard time at the moment

I look forward to hearing from you. Regards. Ron craig