I was born and bred in Poole, Dorset and lived there with my parents until I was about 18. When I left school, I went to live in Africa for a year. I’d suggested to my parents that I could go to University but they discouraged me from embarking on that as they knew it wouldn’t suit me, which was very honest of them. I’d had a place to do Product Design at University, but realised it wasn’t what I wanted to do. I grew up in an environment at school where the emphasis was to go onto university whether it was the right thing to do or not.

During my school years and after I had tried to be a rock star but failed miserably. I played the bass guitar and ended up learning to sing as well because we couldn’t find a singer who could work and produce the kind of music we were doing. This was during a period from 2008 when I was about 16 years old until I was 20, and to put it in perspective, our band was called ‘The Excitable Boys’, a name inspired by a song from Warren Zevon.

We kept the band going throughout school until I was about 23. Then I gave up on being a rock star and realised and accepted that I had to get a job. By that time, I had started cooking.

Even when I was in the band I was always into hospitality, working 4 days a week, in 2 pubs, even 3 pubs at one point to supplement the band life. I managed to work long hours then, like I do now. I had a construction job as well.

Around the time when the band broke up I met up with this lady, Naili (my current business partner) in the local pub near my home in Dorset and asked her for a job. I had previously done some cooking in her kitchen, so I thought it would be sensible to get back to it. The band had failed completely and I’d given up my dream of being a musician. It seemed sensible to revisit familiar territory.

My year overseas had given me a passion to travel and I wanted to do more. I knew if I could cook, I could work anywhere in the world. I did a very brief cooking course, just a basic one. I had looked at other College courses, but they all took three years, and I was already 23 years old. I figured the money I would spend on the short course I could earn in those three years. Also, once I was 26, I would be less likely to get into a commercial kitchen, because I would be that much older with less experience. I decided it was easier to get into a kitchen and learn hands-on.

Fast and furious kitchen work

I came up to Surrey and did the 6-month cooking course in Woking. I finished on a Wednesday, got on a plane on the Friday and flew to Australia. I arrived in Sydney in November, without a job. I just basically landed and printed off a load of CVs and walked round and round the city restaurants. I would turn up between 3-6.00pm, to chat to staff while it was quieter.

This approach always gave a better response than when I phoned. I walked in, shook the guy’s hand, gave him my CV in person and said ‘I want to cook’. Obviously with a lack of experience I didn’t have a huge amount of success. I think the only reason I was successful in the end was because the guy didn’t actually read my CV, which most chefs don’t. When I began that day at Aria, I was completely out of my depth but I survived. The long hours tired me out – I remember sitting at the bus stop one morning, watching the bus come around the corner, and thinking ‘Oh here it comes, this is my bus for work’, and just watched it go past!

A Japanese Deba, (fish, butchery knife)

I subsequently moved to another job in a French restaurant which had a very good reputation. I was lucky to get this job on the back of the reputation from my first job at Aria as this would impress people. They would say, “Oh he’s worked at Aria, this guy can cook”. Unfortunately, the Chef there quickly realised I couldn’t cook. It was very traditional French cooking. There were no water baths, no vacuum packing, no squeezy bottles. If a chef put one fish in the oven, I would have to sear two bits of meat to go with it as a garnish, heat up a puree in a pot, maybe some mash potato and some spinach. The head chef himself was very competent, but definitely old school.

We started work at 11 o’clock to be ready for dinner. I remember waking up in the morning, when my alarm went off and getting stressed. In the first restaurant I’d had support and could churn out prep in the morning. In this other restaurant I had to get a section ready and if it wasn’t it would all be my fault that proceedings got delayed. I remember having this 6ft tall Canadian guy towering over me with a tray of spinach, asking “Is this spinach seasoned?” They used to call me Rabbit, because on my first day I just looked like a rabbit in headlights. He just came out with a mass of expletives at me, “****!”, took the tray, slammed it onto my stove and the whole thing went up in flames. I stood there, pan in hand, whole stove in flames and he’s screaming “WHERE’S MY SPINACH?!”, Gordon Ramsey style. All I could do was put the fire out with a tea towel and get back to work. It was that kind of a learning environment – fast and furious and you had to get used to it.

Sourdough after bulk fermentation

I moved to New Zealand and worked at a large seafood restaurant down by the docks. I was working on the fine dining side. One day we started buying in whole salmon. The quality of fish was amazing. It was coming in on the day boats from New Zealand, which has some of the best fish. I’ve not had fish like that in a long time. We started filleting this salmon but I had no training and didn’t do it very well. The head chef looked at it, then at me and said, “You’ve buggered that up haven’t you?”, and didn’t do anything else. Fortunately, there was a Japanese guy working there, who now lives in Bangkok running his own restaurant. He taught me how to use the different knives and how fillet the salmon. I stayed in that position for just under 2 years.

Then in the New Year I went with my girlfriend to New York for two or three months, looking for work. I was offered sponsorship for a visa but it wasn’t what I wanted. My girlfriend was a bar tender and she couldn’t get sponsorship at all. I kept applying for jobs and got to see some amazing kitchens such as Eleven Madison Park but there was no sponsorship I could secure. So I landed back in London, determined to look for work again. It was all or nothing.

Laying out the Sourdough to scale it

I was offered a job but the pay was just £16,000 a year. I wanted to work there for the experience but knew I couldn’t live off that money, it wasn’t possible. Eighty hours a week for that wage just didn’t sound right. So I worked as a pastry chef for 6 months at Marcus Wareing’s restaurant at The Berkeley. That was really invaluable as I’d never prepared pastry before, it showed me a whole new side of things.

From there I had an opportunity to work with an old friend from cooking school, in a little barbecue restaurant in Soho, named Pitt Cue Co. The restaurant had begun as a food truck. Then someone, who was quite famous sent a tweet about it and the next day there were hundreds of people turning up. Gradually the business built up and the restaurant evolved.

Starting to shape the loaf

It was very much a developing kitchen, which is why I think I stayed so long. Each time we thought we had learnt everything we could, someone would bring in a new technique or a new piece of equipment, which we would master and make progress.

Over the years I’ve worked in many different kitchens. Working in the London restaurants during exciting times like the Olympics 2012. Working through the heat waves of 2013 and 2014 in a basement kitchen where I’ve no idea how high the temperature was. The people I’ve worked with are still close, we keep in touch. Always working hard, long hours.

Stage 1 of shaping Sourdough bread

When I was in cooking school, I did 2 weeks work experience, during a break at a bakery, in Long Crichel. It was my first commercial bakery experience, with a big, wood-fire oven. There were a couple of polish guys baking there who made it look so simple. I still have some really good recipes from that bakery.

After Pitt Cue Co. I worked in a Japanese sushi restaurant, NoBo and learnt a bit about the processes required. The experienced sushi cooks are quite closed about their style of cooking. They suspect cooks will steal their skills. So the head chef, the best, most knowledgeable guy is at one end of the bar. The better you are, the closer you can work with him. The junior chaps are the furthest away from head chef and the seniors are the closest. You’re supposed to observe the guy next to you, watch how he’s cutting and then one day there may be an opportunity where he says cut this and you can just do it. You move up the ‘ranks’ on that basis.

Stage 2 of shaping Sourdough bread

From Nobo I went to work at Kitty Fishers, which was a wood fire grill restaurant. But by then I was getting bored, because I was moving around but not learning anything or progressing. I wanted to take things up a step and start my own restaurant. I messaged Naili, the lady who had given me my first cooking job down in Dorset. I sent her a message as a joke asking if she wanted to buy me a pub.

By then I had started to look for a business myself and was thinking of pushing for a restaurant and bar as well. Unknown to me she had messaged me earlier asking if I wanted to come and open a restaurant with her but for some reason, I never received her message until a long time later. When I did receive it, I was delighted with her proposal and we ended up taking over The Fox Inn, Rudgwick. It was all very sudden and quick at the time.

Stage 3 of shaping Sourdough bread

I left Kitty Fishers in 2015, we started at the Fox Inn on the 29th September, with literally a week’s notice that we were coming in. When you’re looking to start a business, you’ve got to go for it.

When seeking a new business, I knew I didn’t want to go back to Dorset and be too far away from London. Naili basically chose this pub for me. I didn’t really get a choice. The Fox was available, we knew we could work with it. I knew by then I just wanted to be the owner of a restaurant and be in charge, later on I could make adjustments. Which is what we’re doing now. Tereza and all the staff have been a massive part of the adjustment. There are things we do now that we didn’t have the model for when we arrived. We make the bread now but that wasn’t on my mind when we started. It’s always been something I enjoy and it naturally evolved here due to the location.

Stage 4 of shaping Sourdough bread

It was a shock coming here in the same way that going to Australia was. I was completely out of my depth. I didn’t really know what I was doing. I just sort of jump in life. I’ll stay at a level for a while and learn at that level, then once I’ve done that I’ll leap, I’m not a gradual climber. I skipped being a head chef, I skipped being a manager, I skipped all of these and went from being a chef, a nobody, to being a director of a company running a pub. The first few weeks here were crazy, I was still commuting from London.

We’ve made a lot of mistakes along the way, learning all the time.

Scoring the loaves

Making our own bread came out of necessity.

Initially we would order baguettes, brioche and buns from a local supplier. But there had been a couple of weekends where they’d been short staffed and were unable to deliver our order and it became apparent, we had to start making our own bread.

Scored loaves ready to load

We began playing with recipes, most of which required a lot of hand mixing and a dough mixer. Then I was kindly given a 10-year-old Sourdough starter by a regular customer, which is a fermented mass, filled with natural, wild yeast.

The Sourdough starter is what makes Sourdough bread rise.

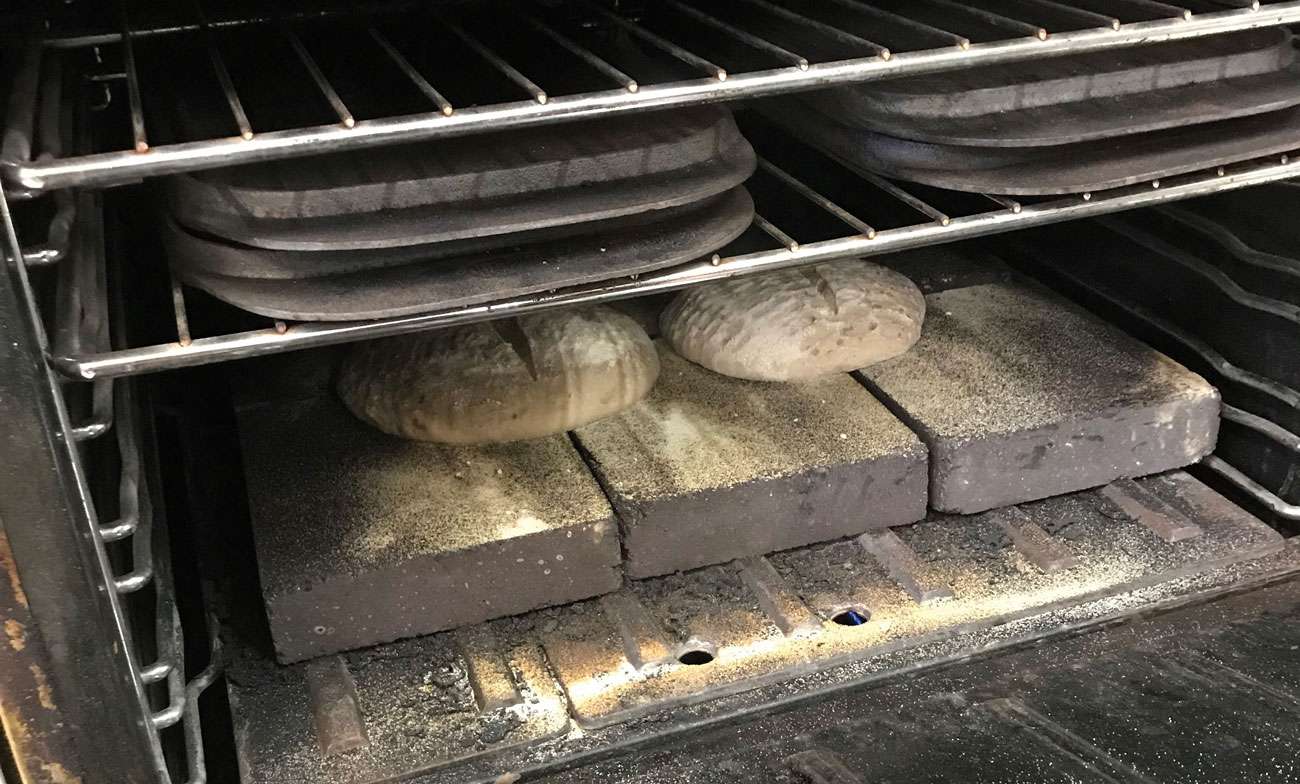

Finally into the oven

Once we were confident we could make our own bread, we spent a long time playing around with the recipe. There was a lot of trial and error but once we got the recipe right with the normal flour, we then moved onto the organic flour. The recipe didn’t go quite as well and we had to make some little tweaks.

We began to use Gilchester’s organic flour from up north. We could have used normal white bread flour, which produces a lighter loaf, but the flavour of Gilchester’s was too great to pass up. Gilchester’s flour is stoneground and relatively unprocessed, a lot of “impurities” remain, which gives a superior depth of flavour, almost like an unfiltered wine. Because its unprocessed, every year is different.

Just out of the oven

The only three ingredients are sea salt, which we buy from Scotland, flour and water. We follow a similar technique to Tartine, which is actually a really old traditional style. There are two choices of technique – to subject the dough to a very intense amount of movement over a short time, or drag it out over a long time and do a lot of stretching and folding.

Every half an hour, we go back to the dough which we keep at a low temperature, to stretch and fold it out. Essentially, you’re ‘laminating’ the dough and not only is that building and exercising it, it’s producing structure inside the dough. That means we can make a 10-kilo dough without using a machine, we do it all by hand. It’s a technique they used way back in traditional days when bakeries produced large quantities for the villages, without any machinery at all.

One of our Sourdough breads

The salt in the bread helps the gluten network provide structure. If you put in a wholegrain wheat, essentially it cuts the gluten, and damages the structure which is why something like a wholegrain will be a heavier, denser loaf as the structure isn’t strong enough to aerate as much. We had to play with the salt content to provide the extra strength to get the structure we wanted.

The next problem was the oven. Commercial bakery ovens cost £5,000-£10,000 and we couldn’t afford that. We were baking at a very high temperature, 250oC, on a stone floor. A residual heat is required that isn’t attainable with a standard oven because when you put 4 kilos of wet flour into a standard oven, it tends to suck the heat out of the metal structure. You need bricks at the bottom to retain the heat, even though it might get sucked out a little, there’s that gentle force. So we ended up filling one of our gas ovens with 16 firebricks, different to the ones we’ve got now, and a few other additions.

The crumb

A modern bread oven injects a load of water that forces the bread to come into contact with the heat much faster and moistens the outside of the dough so it’s stretchier because the dough’s wetter. It adds a shine to the crust and does a multitude of other things that we unfortunately couldn’t do with our oven.

All we’ve done is get a little bit of tin foil to block up some of the air vents on the back, which means that when the bread goes in, the moisture doesn’t leave the oven as quickly as it might. It’s similar to how they did it in the old days, when they had a wood fire oven. They would put the dough in and close the door, sealing it completely. The moisture came from the dough itself. When you’ve got a wet dough, the moisture evaporates and fills the oven with moisture. That’s your 10-15 minutes of oven spring, after that time the breads not going to get any bigger, the outside has set where it is and the more you cook it, the less moisture will come out. In turn the less moisture in the oven, the more brown it gets. So it’s kind of like a self-making system. The best way to simulate this at home is using a Dutch oven.

Barrel fermented brandy

Our homemade bread has become more popular since people discovered we were producing it. It began out of necessity because of supply issues and has become something that makes us unique. Also in another sense, it makes us happy because every morning we venture downstairs to bake fresh bread. When you have a bad bake, which can happen, it’s very upsetting, but when you have a good bake it’s really satisfying.

It takes a certain person to be excited about flour and water. It’s certainly a slow process we use. It is essentially a 36-hour process.

The Fox Inn, Rudgwick

Something I was taught in the bakery when I was younger, was these modern breads are made very quickly and the yeast doesn’t have time to naturally act on the gluten, and doesn’t process it properly. This is why all of a sudden there are a lot of people who are gluten intolerant which didn’t happen before. With our technique the slow fermentation gives the yeast time to act on the gluten, which makes it more digestible.

Any bread dough created is dependant on many conditions. For example, it’s necessary to have the right percentage of water to flour. If you live in a wetter country the flour’s going to hold more water naturally just from the humidity in the room than if you live in a dry country. So recipes are always going to change.

Lamb shank with vegetables

Once you’ve learnt the science and understanding of what each individual component does and why the glutens lower, then essentially you have to put that aside and begin each morning by examining the starter and ‘feel’ it. If you come down in the morning and it’s been cold, the starter might not be ready. You can’t just jump in and make the bread as usual because it just won’t work. You have to be patient and wait until it is ready. It’s a bit of a waiting game.

If I was to loose my Sourdough starter, I would’ve lost 14 years of flavour, history and depth. You can’t just manufacture that flavour and depth. I’ve got my yeast that I was lucky enough to be given, made naturally by the flour it was fed. This creates the unique starter, which in turn makes the bread what it is. All starters are slightly unique. I could take my starter and gradually feed it with a different flour (change it’s diet) that will make it a different starter every time. But it doesn’t happen overnight.

Sourdough bread with egg

Making bread is a thousand-year long tradition across the country.

Looking to the future we are working on a few exciting things that should be operational in the coming months. We are going to introduce our own local beer at The Fox,

by taking some of our bread waste and using it in the production of the beer. Recently we’ve produced our own local apple brandy, which is on sale now. As a new venture, we are showing outdoor movies every Saturday evening while the weather stays good. (See our advert on page 20 for more details.)

At the Fox, we always strive to source all our ingredients naturally from local producers and suppliers, just like our bread. We reap what we sow. ![]()

Very interesting article – reminds me of the regular column in the Financial Times many years ago, entitled “Other Men’s Jobs”. A bit of a sideways look at the way other breadwinners ‘win bread’ (or make it, in this case).

Well done for correcting the spelling error in the printed copy of August’s issue: Restaurateur, not Restauranteur!