In Greek myths it never pays to be boastful before the gods. The young Arachne was a wonderful weaver and as Ovid writes in his Metamorphoses she had the temerity to challenge the goddess Athena to a tapestry weaving contest. Bizarrely Athena was the goddess of war, handicrafts and reason – which seem like an unlikely and contradictory collection of things of which to be a goddess.

The story is that Arachne wove the better tapestry – without a flaw. Athena was so outraged she beat Arachne with her shuttle – and the young girl, after hanging herself in shame, was turned into a spider. Hence spiders ‘weaving’ webs and the family of the creatures being known as arachnids.

All summer I have swept little silk-covered spider ‘presents’ from the windowsills of my conservatory. Desiccated bodies of flies, bees and butterflies, tightly bound and sucked dry. I try and rescue the butterflies and bees when I can, but leave the flies and am happy with this natural insect control.

We have also had a large garden spider which lurked by my front door, in the light fitment. We called it Fred and had taken to greeting it. Last week I had the front door open for a while and Fred took the opportunity to nip into the hall and lodge on top of the mirror. Obviously he decided that being an indoor spider was preferable now that winter was on its way – although garden and house spiders are two distinct arachnid families. I scooped him up and put him outside again – and I am waiting to see if he tries that trick again.

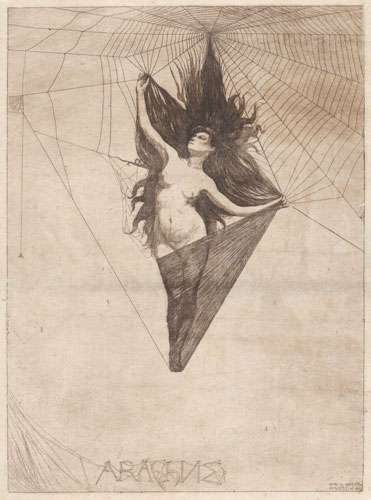

‘Arachne’. Etching by Otto Henry Bacher 1884

People have reported more spiders than usual this year and one correspondent to The Telegraph has written that it has been calculated that an acre of land can house two million spiders. That’s about 40,000 in a small garden of 10 by 10 yards. He adds that an abundance of spiders means an abundance of insects, which indicates a healthy environment. Good news, except for arachnophobes.

Not all spiders weave webs including the white crab spider and the wolf spider, both of which chase their prey, rather than trapping it. All spiders have the most intriguing leg mechanism. Instead of using muscles to extend the major leg joints, a spider uses hydraulic power – pumping liquid into the legs, which under pressure push the joints outwards. That is why a dead spider’s legs look so feeble and flabby; no pressure. This has been described as a ‘design masterpiece’ and explains the great agility and speed of spiders’ movements.

I grew up in a country with tarantulas and a spider called ‘pollito’ meaning ‘little chick’ – which was about the size of my hand. This spider paralyzes the chick, drags it into its hole and lays its eggs on it – so that the spiderlings have fresh meat to eat when they hatch. This is not a unique trick in Nature; plenty of other insects do this; gruesome but effective.

One of the beauties of autumn is that cobwebs become visible in all their intricate detail. It is hard not to marvel at the beauty, variety and skill of the spider. There are horizontal and vertical webs, some have funnel entrances, others are closely woven mats of silk.

‘Fred’, hanging out in our garden

From earliest records, humans have used pads made of spider webs to staunch bleeding. There is something in the web that promotes blood clotting. As with all these folk remedies, one wonders how this was first discovered? Over thousands of years did people keep treating wounds with anything to hand like, maybe, seaweed, oak ink or scummy pond water until that Eureka moment when they discovered something which actually worked?

If you have read Helen MacFarlane’s book H for Hawk – you will enjoy her latest titled Vesper Flights. It is a collection of essays on a variety of topics – but the unifying thread is our problematic relationship with Nature. We are apparently hardwired not to see large existential catastrophes looming, and that evolution has made us only able to cope with the small and immediate. Shortly world leaders will be jetting in for COP26 to discuss and promise solutions to the challenges of climate change. Let us hope that some real progress is made.

Photos supplied by Mark Matthews Beryl Harvey Fields is Cranleigh’s nature conservation site. We need volunteers. For further information: visit our conservation site in Cranleigh – or better, volunteer. Contact Philip Townsend at: townsendp99@gmail.com for details.

Find out more about the Beryl Harvey Fields HERE.